Plots, Plats, and Surveys: Mapping Peaks Island

Maps are rich historical sources that can help people visualize the past, and how geographic places have changed over time. The Fifth Maine Museum collection contains many maps, plans, and surveys, and they document how Peaks Island’s land was used over the past 150 years.

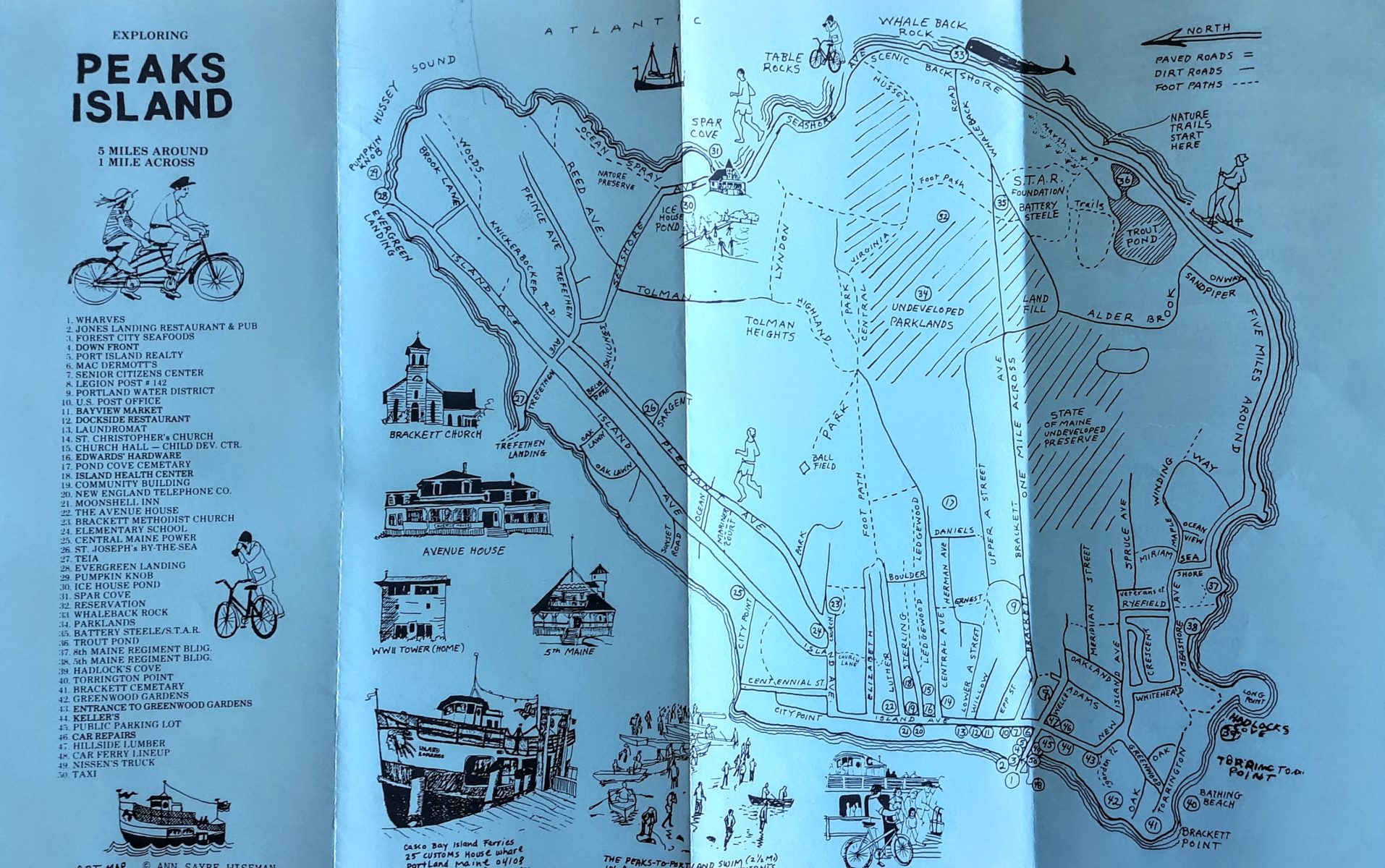

Map, Exploring Peaks Island, circa 1980. This ephemeral map was intended for tourists and day trippers.

Map, Exploring Peaks Island, circa 1980. This ephemeral map was intended for tourists and day trippers.

At the most basic, macro level, these maps document basic factual information: Where the neighborhoods, streets, roads, bodies of water, and other geographical features were, and what they were called. Drilling down into the micro level, they can reveal much more about the relationships between families and neighbors, what kinds of businesses flourished, and which struggled and failed, and even how the natural environment, such as forests and marine resources, are utilized or protected.

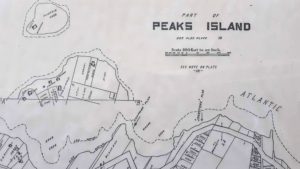

Survey detail, “Part of Peaks Island,” circa 1905, showing part of the back shore of Peaks Island,

Survey detail, “Part of Peaks Island,” circa 1905, showing part of the back shore of Peaks Island,

including the various coves, and the high and low water marks.

Considering who the intended audience was is important when using maps as primary source documents. It’s unsurprising that many of the mid-to-late 20th century maps in the collection are ephemeral and were intended for day-trippers and other short-term visitors to the island. Many of these maps weren’t drawn to scale, but are helpful in showing what businesses existed at the time, and where they were located.

Survey detail, “Part of Peaks Island,” circa 1905, showing what is now the

Survey detail, “Part of Peaks Island,” circa 1905, showing what is now the

Fifth Maine Museum on what was then called “Oceanside Avenue

Land surveys are pretty much the opposite of the ephemeral tourist maps, in that they are drawn precisely to scale and every foot mattered. Some survey maps show the owner’s name, the footprint of the building(s) on the property, and sometimes, especially on insurance maps, what material the buildings are constructed from.

Survey detail, “Part of Peaks Island,” circa 1905, showing the precise location of the

merry-go-round, moving picture cinema, and the bowling alley at Greenwood Gardens.

Some maps were speculative. Peaks Island has had various subdivisions and real estate developments over the years that were planned on paper, but never came to fruition in real life, or at least not at the scale that was originally envisioned. May Chapman’s “Rock Bound Park” was one such development on late 19th century Peaks Island.

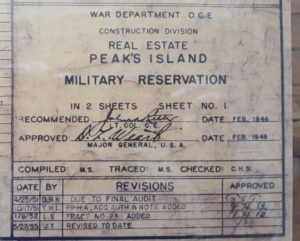

Title block detail, “Real Estate Peak’s Island Military Reservation,” 1946-1955

Title block detail, “Real Estate Peak’s Island Military Reservation,” 1946-1955

Even the most didactic survey can reveal a poignant human story. One map in the collection includes an “Acquisition Tract Register,” which lists the owners of nearly 200 acres of land seized by the government by eminent domain in order to construct the the Peaks Island Military Reservation during World War II. Some island families were unhappy to relinquish their land, even for such a just cause.

“Acquisition Tract Register” detail from the map, “Real Estate Peak’s Island Military Reservation,” 1946-1955.

“Acquisition Tract Register” detail from the map, “Real Estate Peak’s Island Military Reservation,” 1946-1955.

More than simply visualizations of space and geographical relationships, the maps in the museum collection tell stories of the island and the people who lived there.